On this page blogs will be published about artefacts (or: objects) connected with the Viking period. Preceding blogs can be found under the newest blog.

August 28th 2025

For collectors who want my advice concerning selling their collection (or otherwise)

Lately, I’ve been receiving—suddenly—questions from collectors (or: metal seekers) asking me about Viking Age objects in their collections, asking for advice on what to do with them now that they want to find a new purpose (sell them or transfer them to an institution for further research).

After some further questioning, it turns out they want to sell their collection because they need to make money from one thing or another.

Because I want to manage expectations, I’m writing this blog. First of all: I offer advice on Viking Age objects. This concerns authentication—is it genuine/period; is it Viking Age or not; is it Viking at all—based on its decorative style or shape.

In doing so, I often research the object in question, and if the object’s decorative style or shape is beyond my immediate recognition—a process I’ve accumulated over more than twenty years—I consult sources, delve into new ones, and/or seek advice from other experts if I still can’t figure it out, which doesn’t happen often. If I truly can’t give a satisfactory answer, I will be upfront about it.

When someone asks me for advice on what to do with their collection, I can offer advice from the perspective of someone who wants to sell it. There are several options, and the primary consideration is the intended purpose of the collection. Is monetary return the primary consideration, or is preserving the objects in a consistent environment with a consistent story about their provenance and interpretation?

Personally, I favor the latter, because someone with an object from the Viking Age, acquired through their own discovery or through collecting, is only a temporary holder of an – often – unique object.

What should you do in that case? A few tips:

If the collection originated from personal discoveries, then the context is obviously much more valuable than objects purchased “loosely” online without (satisfactory) context. Keep this in mind. True collectors—or: museums—with a passion for preserving this unique piece of material history will view the objects through this lens throughout their lives, seeking out their contextual value and/or preserving them for future generations who will want to marvel at them, conduct further research, or, simply, appreciate that these objects—under the radar of current researchers in museums or institutions/academics—may, at some point in the future, provide contextual information and interpretation for (currently) unknown finds, or finds gathering dust in a museum’s depot, that will one day resurface.

If you agree with such an approach and recognize that preserving objects is of greater intrinsic value than making money from them (are you listening, auction houses?), then the way to go is to contact local museums. The question then becomes whether the museum (or other official institution) is interested in incorporating the objects into their museum. They might want them, but what actually happens with them? Will they be exhibited? Will it disappear into storage? Or will it be further investigated/made available for research online or on-site? How do you “see” your collection (or: object) in such a museum, and do you have any wishes or expectations that the museum in question can accommodate?

If you’re more of the “other school” and want to sell your collection, there are other options. However, don’t overestimate the online interest in terms of potential revenue. Auction houses nowadays charge a 24% purchase fee and will often deliberately conceal the provenance if they think there’s money in it for them. On online auction sites like eBay or Catawiki, the selection of “junk Viking items” is so vast that I doubt there’s still a “public” there that recognizes or appreciates authentic Viking Age objects (given the many sales of objects that have absolutely nothing to do with Viking artefacts). Then look for smaller, reputable antique sellers with their own websites, who, at all costs, preserve the provenance and story for a future owner.

I am not a seller. If you choose the latter option, then you are the seller. First of all, I don’t know you and I won’t bet on the provenance of the objects you have in your collection and show me. That is the owner’s own responsibility.

The philosophical core question here is perhaps this:

What do you want to be: an owner or a custodian?

I hope these ‘tips’ provide some insight into my approach when it comes to advice and prevent and answer some questions—or, more importantly, expectations—in advance.

As always, I am happy to assist you in this philosophical consideration.

November 25th 2024.

A rare Viking Age pommel cap, found in Friesland.

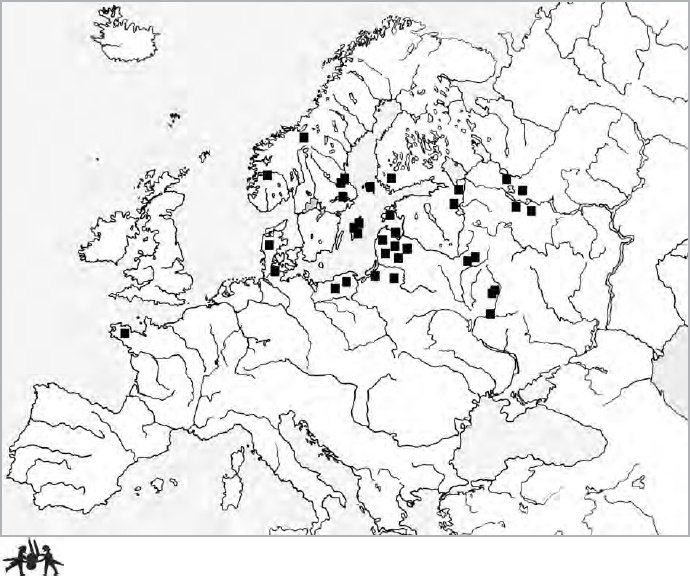

Objects found in the Netherlands that can be described as ‘Viking’ – loosely translated – are extremely rare. Of course, there are the well-known objects from the Viking Age, which were found at Wijk bij Duurstede – the former Dorestad –, the silver treasures of Westerklief and the objects with a Scandinavian or ‘Frisian-Scandinavian’ decoration style, found in the 19th century on the beach at Domburg, in Zeeland. In addition to these, already older, finds, a gold or bronze ring is very occasionally found that, mainly based on their design, can be attributed to the Viking Age. However, objects with an unmistakable Scandinavian decoration style, as was in vogue in the Viking Age, are very rarely found. They can be counted on the fingers of – at most – two hands.

With some regularity, metal seekers show an object they have found, always asking whether it is ‘Viking’. Always, or: almost always I have to disappoint them because the piece in question does not meet the definition. Often such an object is from the early Middle Ages, but in terms of shape and/or style it cannot technically be assigned to the ‘Viking Age’ – which is also a concept that was formed in retrospect. The inhabitants of – the part of Northern Europe now called Scandinavia – of course did not have a ‘Viking Age’ at the time of the Vikings.

As mentioned, the objects are then still early medieval, but then to be described as Ottonian, or Frankish and sometimes Carolingian.

The undersigned is then very excited when Sander Visser, a metal seeker, reports with a so-called pommel cap he found – the upper part of a sword – with a suspiciously Scandinavian-looking shape, but above all: decorative style. Just for the layman: The sword pommel consists of two parts; the pommel cap and the crossguard underneath. The pommel cap found by Sander Visser dates from the first half of the 10th century. Later in time we come across pommels that consist of one piece and are therefore only called pommel. The pommel cap is the upper part of the pommel, the pommel is the part of a sword that provides a counterbalance to the end of a handle of a sword or a knife. The name pommel comes from the Latin name for “small apple”.

The first photo that is shown – and that I get to see – is how the pommel cap was found. The shape and the decoration in the middle of the pommel cap already raises an eyebrow of excitement in me; yet I am still cautious. This is partly due to unfamiliarity with the type of pommel cap.

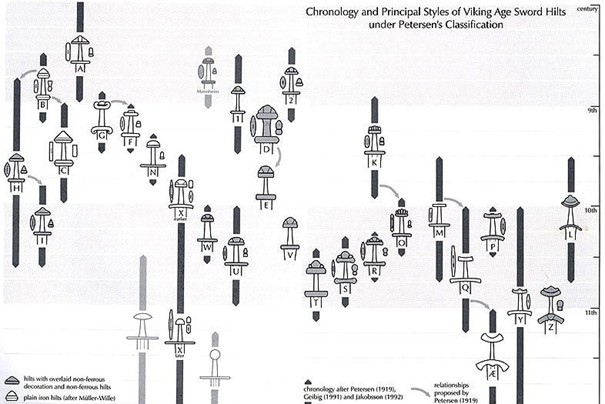

Of course, the scheme that Jan Petersen designed of time chronology and types in sword handles from the Viking period is already over a hundred years old, and, in particular, metal detection, has of course significantly expanded the catalogue of pommel caps and pommels, certainly in the past twenty to thirty years. Petersen based his typology of 26 types on 1,700 finds of Viking Age swords found in Norway.

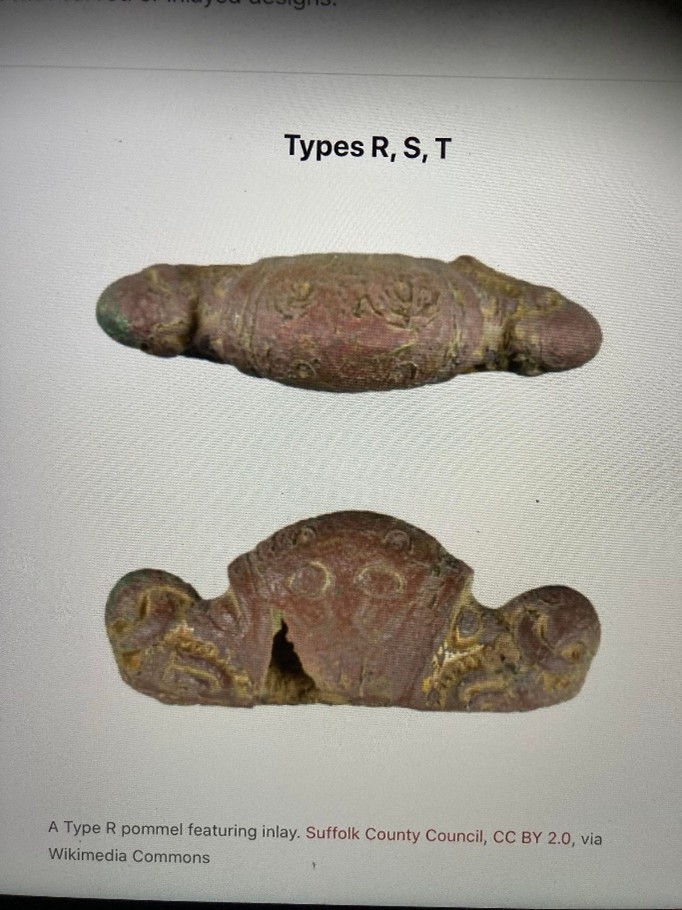

Raker typified is type R within the classification scheme of Petersen, as a find from England shows, and then specifically within this type R, type III which is found mainly in the northwest of Germany and southern Scandinavia. This shows, in addition to a somewhat wider central part, on either side two animal (resembling) heads, probably boar heads, in, what James Graham Campbell, the well-known authority when it comes to publications about the Vikings and the decoration styles from the Viking period, calls a hybrid or: transverse Borre/Jellinge style and thus gives a dating of 925 – 1000 A.D.

Ny Björn Gustafson noted: ‘It is like a transitional mix between Wheeler’s type III/Petersen R, i.e. two (more or less) beaked heads, and Wheeler’s type IV/Petersen O, i.e. “five knuckles” (five-lobed type, ed. ) It is hard to tell wich way it is going in terms of design, but it has some traits (e.g. the snouts) in common with this W/IV/Petersen O pommel from North Yorkshire in the PAS (Portable Antiques Scheme, ed.) database https://finds.org.uk/databse/artefacts/record/id/995783.’

An exactly similar type, though fragmentary, was purchased by a collector of Viking objects in California, 45 years ago, from a person in the north of England.

This one also has traces of silver and gold. This collector believes that the pommel cap comes from the period of the so-called Danelaw – an area in Northern and Eastern England colonized by Danish colonists in the 9th and 10th centuries. The finder of the pommel cap from Friesland concluded from this that this type of pommel cap came from Denmark with Danish Vikings around 900. This is possible, but for me it is not a foregone conclusion (that these would come exclusively from Denmark, ed.). Caroline Paterson gave this response:

‘I am no expert on this pommel type, but it would appear to belong to Petersen’s type S, though is clearly closely related to his type R with its prominent animal-head terminals. Although this type is found throughout the Scandinavian world (though rare in Sweden according to Androshchuk (2014) and Norway – though there is now such a find from Leirong, Tysvaer). Most finds appear to come from Denmark, England and also Gotland. Although with a distinctive curved base and raised central portion (more in keeping with type L hilts) the high quality Anglo-Saxon pommel from the Seine, Paris (Wilson 1964, no. 66, 166-7) with its filigree panel may be an early forerunner for the type with its pair of outward facing animal heads. Moreover, Fuglesang and Petersen both regarded the type as being based on West European models, but later the ornament is more markedly Scandinavian in style. Interlace executed in the Mammen style decorates the central dome of the pommel from Grasand, Denmark (Fuglesang 1980, Pl. 15 B-C) and several of the English finds have a stylized en-face Mammen style human head in the central lobe and Jan Petersen refers to some Scandinavian parallels for this (173-4).

There is an interesting online article (A Viking Period Metalworking Hoard from Alvena in Mästerby parish, Gotland, ed.) on a find from Pacuiul lui Soare, Romania which discusses the group and illustrates some of the finds from Gotland – including the five Alvena pommels which were unfinished. I wonder where your Frisian find was manufactured? Perhaps Gotland or even England?

The article A Viking Period Metalworking Hoard from Alvena in Mästerby parish, Gotland deals with a find made in October 2010 on Gotland in which, in addition to fourteen found – semi-finished – so-called fish pendants, also five – again semi-finished – pommel caps with – somewhat – similar animal heads on either side of the pommel.

But back to the find from Friesland. ‘Viking’ or not, the finder had made a fine find. The photos of the pommel cap after conservation (by Johan Langelaar, ed.) really made the undersigned enthusiastic. It was here that it became clear that we are dealing with an unmistakably Scandinavian, if you like: ‘Viking’ decoration style pommel cap. Traces of silver colour and gold can be found on the bronze – copper alloy – pommel cap. The dimensions of the pommel cap are length 70 mm and width 20 mm. The height is 30 mm and the weight is 60.3 grams. It is made of a copper alloy that has been gilded.

The middle section shows an intertwined decoration, typical of the Jellinge style, which ends in a – seemingly – heart-shaped spiral, as I have also seen on small fittings from the Baltic area during the Viking period. This makes this pommel cap exude “two worlds” for me. The – very clear – world of the Vikings, given the decoration and shape of the animal (resembling) heads and a partly Slavic-looking decoration at the top of the middle section. It is Scandinavian, but not completely. The inwardly circling shape at the top of the middle section is reminiscent of a bronze fitting found in Grobina, Latvia. The two – considered to be boar heads – on either side have a hybrid Jellinge / Borre style decoration. First of all, it is fortunate that the decoration has been preserved so well. Many objects have been seriously damaged and/or eroded over the last twenty years by the use of artificial fertilizers, which has all too often had a devastating effect on bronze objects.

The distribution area of this very specific type of pommel cap – north-west Germany and southern Scandinavia – clearly shows the possibility that this pommel cap could have been brought – and most likely made – in/from one of these areas. We must therefore look at the object itself and then we can call it a ‘Viking’ without further ado, purely because of its decoration style, nor apart from the ultimate function it had. Because these are of course two different things.

The pommel cap is of course part of a so-called loose find, without further context. If this pommel cap had been found together with – demonstrably – other Scandinavian objects, then the find spot could indicate a (small or larger) settlement of people from Scandinavia in this part of Friesland, which at the time extended from Zeeland to Friesland. Such a – most likely – settlement in the Frisian area was Walcheren, where various objects with a Scandinavian or, as I described in Vikings and the objects from the Viking Age (2023) ‘objects with a hybrid’ Frisian-Scandinavian decoration style.’ It would have been even more spectacular if this pommel had been found in the context of a grave. But both – with emphasis: possibilities – are not relevant here, for the time being, because the find is a loose metal detector find. However, that may still change, because the Fries Museum has been granted exclusive access to continue searching in the soil where the pommel was found.

This does not make this find inferior or secondary for the undersigned. On the contrary: it is one of the most exciting finds made in our country in many years. It shows, once again and unmistakably – for those who still doubted it – that there was a Scandinavian presence in our Low Countries. Although this is (still) difficult to see in archaeology, it must have lasted longer in certain coastal areas of the area that used to be called Frisia and that ran from Zeeland to beyond Groningen. An aspect that is still relatively unknown to many is that Frisians themselves sometimes went on raids or traded with these Vikings as mercenaries or out of conviction. Some Frisians were therefore themselves subject to Viking behavior. It is therefore very possible that one of these two aspects caused the pommel cap to end up in the ground near Witmarsum. To be found again a thousand years later.

The object could therefore have been part of a sword that was used for fighting, or it could have had a decorative value and was exclusively associated with it.

A book or novel could be written about this beautifully decorated pommel… for those who can imagine it!

In the meantime, the pommel has been registered with the Dutch equivalent of the PAS, the PAN (Portable Antiquities Netherlands, ed.) under number PAN-00156039 and has been given a place in the Fries Museum, where, after first being exhibited in the National Museum of Antiquities, it will have its “final resting place”, in the heart of the province where it was found.

Sources:

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pommel

http://www.vikingage.org/wiki/wiki/Swords

https://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:537484/FULLTEXT01

Gustafsson, N.G., A Viking Period Metalworking Hoard from Alvena in Mästerby parish, Gotland, Fornvännen 106 (2011)

https://finds.org.uk/databse/artefacts/record/id/995783

https://www.portable-antiquities.nl/pan/#/object/public/156039

https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/article295985799.html

Thanks to: Sander Visser, Caroline Peterson and Ny Björn Gustafsson.

October 30th 2024.

Often overlooked: the viking horse harness cheekpiece part.

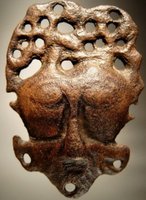

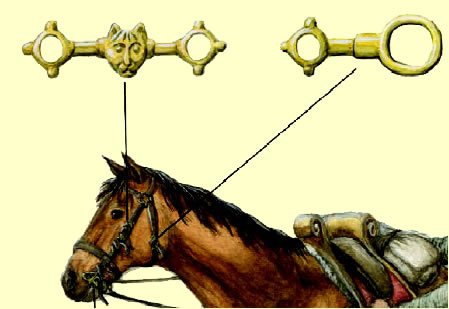

In this blog I’d like to discuss an – easily overlooked – object type from the (late) Viking period, wich have been found, be it scarcely. The horse harness cheekpiece part imaged hereunder had been found in Norfolk and is measuring 5,7 centimeters in length, 4 centimeters in width and weiging 24,13 grams.

The (late) viking horse harness cheekpiece (part) is somewhat puzzling when it comes to terminology. Being it the proper describtion, it also is being categorized as ‘harness fitting’, ‘bridle fitting’, ‘bridle cheek’ piece and even ‘bridle bit’ (object types decribtions used by the Portable Antiques Scheme).

The horse harness cheekpiece – both described as ‘cheekpiece’ as two seperate words ‘cheek piece’ linked the end of the bit to the cheek strap of the bridle. The so called cheekpiece thus belongs to the horse harness and would have been attached to the reins, allowing the rider to control the horse. Sometimes fragments of this cheek piece are being found. Complete cheek pieces being found are extremely rare, because the way of their use. The fragment would have been one of two symmetrical loops forming part of an Anglo-Scandinavian horse’s cheekpiece – I will discuss the Anglo-Scandinavian nature of these cheekpiece(parts) further on. These fragments would have joined together at their inner edges with a hole in the centre forming a larger openwork plate. This would then have linked the end of the bit to the cheek strap end of the bridle.

Sometimes this hole has been worn through friction against the bit, causing the cheekpiece to be discarded. It is easily to imagine the fierce force being executed on the cheekpiece controlling the horse, especially in sudden situations. The breaking off of a part of the cheek piece not unimaginable.

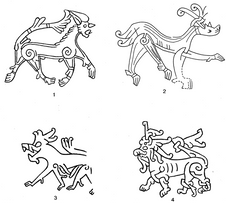

The decoration seen on horse harness cheekpiece (parts) being found in England derived from the late Viking Ringerike style wich was in fashion during the reign of Cnut (1014-42) and may have had a longer life in England. The decorational style is considered as a ‘late viking inspiration.’ The Anglo – Saxon adorers or Norse inhabitants from the Danelaw adopting it and spreding it further – interpretation of the Scandinavian Ringerike style developed into a distinct own style within England: the Anglo-Scandinavian Ringerike style. The cruder form of ornamentation and decoration is characteristic within this so called ‘sub’ or ‘hybrid’ style.

The Ringerike style, named after the place in Norway, first appeared in the 11th century in England. This style was popular just before the Norman Conquest of 1066. The style originated in Norway, but use spread throughout England and the majority of Ringerike objects found in England where made there. After the Norman Conquest the Norman rulers replacing the older ones favoured different styles of art and design, drifting away from the (Anglo) Scandinavian art style into romanesque art style. By 1070 AD seemingly the Ringerike style was out of fashion, though Jonas Lau Markussen argues that ‘The Ringerike style was widespread throughout Scandinavia and all the Norse settlements, particularly in the British Isles, where it inspired many of the local styles, and even found great popularity in the Irish regions, were it was extensively adopted and, among other things, directly inspired a few manuscripts. It continued to be used in this region even after it faded and transitioned to the Urnes style in Scandinavia.’

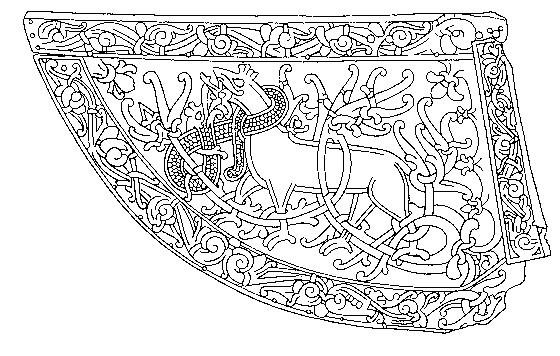

Mostly representing a crudely formed horse’s head, on – much – rarer occasions horse harness cheekpiece parts are being found witnessing a more puzzling – seemingly one-off – design. The example shown hereunder – also having been found in England – is showing the Ringerike style in a more clever, puzzling way.

Although it is virtually impossible to acertain, different images seems to appear turning the part of this horse harness cheekpiece around, recalling the “hidden faces” imagery so often to be recognized in artefacts from the Viking period.

The “beast” could have has a long bill or snout and the body encloses an oval opening – but imagery is, as always, in the eye of the beholder !

See also:

References:

Portable Antiques Scheme England

https://elmbridgemuseum.org.uk/a-special-donation-to-elmbridge-museum/

June 12th 2024

In this blog, David Mullaly shares another intriguing artefact with us from the Viking period.

A reconsideration of a familiar Viking stirrup mount

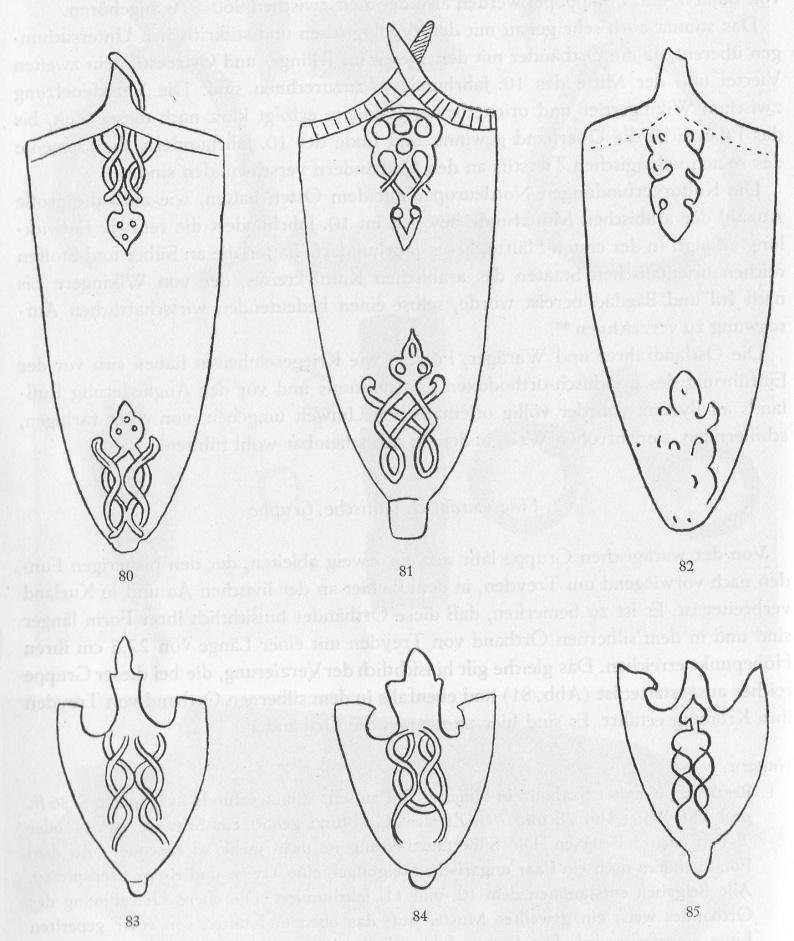

Viking Period bronze stirrup mounts, installed to fasten stirrups to the leather straps hanging down from saddles, are artifacts frequently found in random places. They had a practical design, but it would appear that they frequently failed their riders, with one or more of the three iron rivets becoming loose—and the mount subsequently lost. One of the most familiar Viking stirrup mounts, given the many known examples of the artifact, is the roughly triangular one which David Williams identifies in his Late Saxon Stirrup-Strap Mounts as a Class A Type 8 form. Often displayed upside down so that they look like large wolf heads, these are among the most clearly defined examples which he illustrated:

At their best, the mounts include beast heads which are fairly abstract, and many of the other features are relatively shallow. Williams suggests that a review of examples of this type tends to confirm what appears to be a gradual

deterioration or “debasement” (his word) in form, and he asserts that this type offered the best example of a rapid stylistic attenuation in a stirrup mount. The examples which Mr. Williams pictures above—there are twenty nine in his catalogue—he presents as the prototypes of later diminished stirrup mounts.

That conclusion may have been premature.

In fact, a recent find in Lincolnshire seems to offer an even earlier version of this stirrup mount. Found not far from Boston, the example pictured above is larger—at 63mm—than most of the pictured Williams mounts. In fact, almost all are considerably smaller. More noticeably, the head of the beast at the top is much larger proportionally, and more defined than any examples provided by the author. Interestingly, between the large ears of the beast are two stubby-looking horns. None of the examples Williams provided, or any other examples that I’ve seen, have a feature resembling horns.

Like a few of the illustrated mounts, this one seems to have the remains of inlaid silver wire on what the author labeled as wings. The narrow ledge on the bottom reverse is typical, and unremarkable. However, the raised elements of the beast body seem unusually distinct.

Honestly, I had always believed that this type of stirrup mount pictured a cowering animal, belly up, with its four legs tucked under it, but this example provides a clear winged beast with its back to the observer.

Whether this particular stirrup mount represents an extremely early version of the Class A Type 8, or if it was simply an unusual variant produced contemporaneously is unknown. However, if one accepts Williams’ scenario about the “debasement” of the type over time, then this newly discovered example is likely one of the earliest forms of the type made in the United Kingdom.

June 6th 2024

In this blog, David Mullaly, a long time friend of mine and passionate vikingolist shares an intriguing artefact with us from the Viking period.

A Viking artifact and an appeal for Valhalla

One of the most intriguing and evocative Viking-related finds from the Rus Viking region that has been found – and that’s figuratively covering a lot of ground – is a dark bronze figure of a Scandinavian-looking man with a sword, carrying in one hand what looks like a huge bracelet made from twisted metal. There is no evidence of a fastening element on the reverse or a suspension loop, so the artifact was not intended to be worn. One writer has suggested this subject for the artifact: “the triumphal entry of a fallen warrior into Valhalla with a ring of oath.”

We know that during the Viking period Norse men were often given bracelets or armrings by leaders as a reward for their general loyalty, or fidelity to an specific oath or commitment that was made. And these typically gold or silver armrings were apparently proudly worn. Staying true to an oath was an extremely important virtue for a Viking. If you gave your word, you had to mean it.

The following commentary is from a Russian website: “At the end of the XIX century, in one of the mounds of the Mogilev [Belarus] province, a bronze figurine of a man with a sword at his belt and a circle in his right hand was found (Fig. 5.4). It was wrapped in bark and covered with planks. Exactly the same figurine comes from the Daugmale hillfort in Latvia. Several works are devoted to both finds. F. Balodis considered the Latvian figurine as an import from Sweden. According to E. S. Mugurevich, both figurines, probably cast in the same mold, were made on the territory where the Daugava – Dnieper route passed. A detailed analysis of these items, undertaken by V.P. Petrenko, led the author to the conclusion that the castings of Latvia and Belarus depict a Scandinavian and both figurines are the products of a Scandinavian artist.” http://ulfdalir.ru/literature/735/2182

Given the description of the context of the find in Belarus, it’s plausible that this type of amulet was intended to be a burial object for a deceased warrior, and thus a statement about his having taken an oath seriously—therefore deserving of a place in Valhalla. Given the obviously pagan aspect of the figure, the item was likely made in the 9th or early 10th century. Whether this type of artifact was made in Scandinavia and brought to the distant Rus Viking lands, or if a Scandinavian craftsman far from home made it, is open to question and further research.

The Daugmale example is currently the only featured and pictured artifact on the home page of the website of the National History Museum of Latvia, indicating its importance. Another example was found near Chernigov in central Ukraine. Including the intriguingly packaged figure described on that Russian website, there have apparently been seven examples found. Each offers a fascinating glimpse into the lives and perspectives of the far-traveling Vikings.

January 10th 2024

Two Viking Artifacts and the Fates

In this blog I give way for an article written by a longtime friend from the States with wich I feel honoured to share the same passion about the Viking period and the artefacts of that time for almost two decades now, David Mullaly.

One of the most distinctive elements of the Norse world-view involved a belief in the power of destiny, which determined how their lives would unfold, and of course how and when they were fated to die. Embodying that sense of inevitability were the three Norse fates or Norns, These were the Norse goddesses of destiny, identified as three sisters named Urd, Verdandi, and Skuld. They lived underneath the world tree, where they wove the strands which make the tapestry of life.

There are historical precursors. Unlike the Norns, the Greek version of the Fates each had a particular function. Their names were Clotho (Spinner), Lachesis (Allotter), and Atropos (Inflexible). Clotho spun the “thread” of human fate, Lachesis dispensed it, and Atropos cut the thread. And the derivative Roman version was the Parcae. Presumably, these earlier trios had a direct influence on the Norse belief in the Norns.

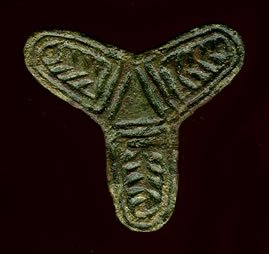

Given the importance of the role of Fate and the Norns for the Nordic people, one would have expected that some sort of representation of them would have been found among the artifacts which have survived, and such would seem to be the case. However, the rarity of those is obvious. One very strange-looking trefoil brooch was found at Kvarberg Hill in central Norway, and is currently in the Museum of Cultural History of the University of Oslo.

A fairly flat bronze three-lobed brooch, it features three large heads with double strands looping into the open mouths from the sides and then out from below the chins. Note that the strands connect to the other heads through a trefoil shape in the middle of the brooch. Although the faces are recognizable, their features are unrealistic, and are closer to cartoons than human heads.

The only commentary I’ve found for that Kvarberg trefoil is in Jan Petersen’s seminal work Viking Age Jewelry (Oslo, 1928) on p.108. There he says that it’s “highly peculiar,” and is a “genuine product of the Viking Age’s imagination.” He also notes that it was an isolated find (and so not reliably datable), but “is clearly characterized by the Borre style” of decoration. He says nothing about the possible subject of the decoration.

Modern jewelry designer David Andersen made many reproductions inspired by that find. Although the contours of the modern brooches are considerably deeper, the basic design is the same: three large heads with double strands looping into the open mouths from the sides and then out from below the chins. Although a large number of this type of reproduction have been sold on Ebay and elsewhere, no one has tried to analyze or even describe the distinctive image.

Another intriguing artifact has been found in the Rus Viking region, and therefore it probably originated in Viking Sweden—or was created far from home by a Swedish craftsman. Like the brooch found in Norway, it has a trefoil shape, but it includes a startling number of differences. First, the faces seem more realistic than the Norwegian find. Although the eyes are bulging, the visage is distinctively human-like, and may suggest an Oseberg style. The shape and details are all representational. The pair of triple cords or strands lead to the chin, rather than involving interlace around the face and under the chin.

The divided shape of the mouth suggests that the pair of triple cords are meant to be seen as emerging from the mouth—perhaps they are speaking the fates of men. There is also a roughly semi-circular emblem on the forehead of each face, which must have had some sort of symbolic significance. As the twin cords leave the face, they cross each other and join with the others to create an interlaced raised mound or boss in the middle with three small balls defining the central trefoil shape. All three faces are linked to each other by the interlaced strands.

Unquestionably the most startling structural feature of the brooch is the pin assembly. Typically, trefoil brooches, and almost all types of Viking brooches, show at least traces of a pin pivot and a catchplate on the reverse. In this case, however, there is a single integral loop on the outside between two lobes, with a long pin and the slight remains of a catchplate on the back. Jan Petersen’s book has pictured thirty-one examples of trefoil brooches, and none of them have even a trace of that loop at the top between the two lobes. I’ve never seen that sort of pin assembly on any trefoil—or any other type of brooch.

There’s almost no possibility that this trefoil brooch was a one-off—a single item which was unique when it was made. Given the labor and expertise which would have been required to make the mold for the brooch, there surely would have been multiple examples made. The casting involved in the creation of this brooch is impressive. The texture covering almost every part of this piece of jewelry suggests great skill and an attention to detail.

Because of the Borre characteristics of the Kvarberg trefoil brooch, a tenth century dating for its making is reasonable. Given what must be described as a much more complex design of the Rus Viking example, an even earlier date is quite likely. One often sees types of artifacts being slowly degraded or attenuated over time in their decorative complexity, and the Kvarberg example seems to be a simpler version of the other one. Plus the distinctive and relatively primitive pin arrangement of the latter hints at an earlier time frame as well. This could be a 9thcentury item of jewelry.

Identifying the imagery of these two trefoil brooches as a representation of the Viking Norns is admittedly conjectural, but it seems as good of an interpretation as any. If only the Norse people had provided clearer cues or commentaries about some of the “highly peculiar” objects they created, our jobs as historians or analysts would be so much simpler. However, they were busy living their lives, and exploring the world that they knew. Ultimately, some of their artifacts, like these two trefoil brooches, simply whisper quietly to us, and we must listen carefully in order to try and decipher what they say.

September 17th 2020

The Elusive Face of the Viking God Thor

In this blog, I like to give way to an article, written by David Mullaly, author of novels about the Viking Age addicted lover of artefacts from the Viking Age, but, above all, a by me truly valued estimated specialist when it comes to knowledge of Viking Age artefacts. My ally overseas and soul mate.

Hereunder he discusses the representation of the Norse god Thor on artefacts from the Viking Age.

In this blog, I like to give way to an article, written by David Mullaly, author of novels about the Viking Age addicted lover of artefacts from the Viking Age, but, above all, a by me truly valued estimated specialist when it comes to knowledge of Viking Age artefacts. My ally overseas and soul mate.

Hereunder he discusses the representation of the Norse god Thor on artefacts from the Viking Age.

The Elusive Face of the Viking God Thor

The two most popular gods in the Norse pantheon were Odin and Thor, and it’s reasonable to expect that the Norse people would want to represent them in decorations on their jewelry and other items. Some artifacts decorated with images of human-like figures, the identities of some of which are unclear, provide a few clear markers for Odin.

If the face has only one eye, and the other eye is unquestionably absent, then the object was presumably intended to provide an image of Odin, the Allfather. He was willing to give up one eye in exchange for wisdom. If the human-like image includes the figures of two birds, Odin again is indicated. He was provided with two ravens, Hugin and Munin, who traveled the world to get information about whatever interested Odin. As I suggested in another commentary, The Odin Mount Revisited – The Converting Element, this supernatural being may also have been represented wearing some sort of interlaced crown or head piece.

Other artifacts featuring a realistic face of a Norse male with large round eyes have been identified as a representation of Odin, although one should take that attribution with at least a few grains of salt.

Finding images intended to represent Thor is more complicated. Of course, Thor has his hammer, called Mjölnir, as a symbol. Many examples of hammer pendants have been found over the years—in gold, silver, bronze, bone, lead. In fact, some were probably made of wood, although long-term survival was always unlikely. However, exchanges with experienced metal detectorists, and by extension with UK Finds Liaison Officers, suggest that some artifacts found with more abstract faces were intended to represent Thor. These are in some cases clearly representative of the “hidden faces” inclinations of Norse craftsmen as I have written about in The hidden face motif in Viking Age artefacts.

Example A is a bronze buckle plate with some surviving gilding, found at Pocklington, near York. A pair of flanking vertical beasts lead one to a crude face in the center surmounted by what might be seen as a pointed helmet, and the beasts become long hair next to the face. This was identified by a FLO as a face of Thor.

Example B is a lead weight or game piece with a gilded bronze insert showing an alien-looking face with an elongated neck and slanted eyes, found near York. Again, a FLO identified this as a representation of Thor. The shape of the head and long neck is similar to faces found on various Norse-Finnic tortoise brooches and other artifacts, but the eyes are very different.

Example C is a more complex artifact. Found near Malton in the Yorkshire Wolds, it is a complete large lead strap end with a minor period repair on the back of the fastening plate. When the item is examined with the flat area at the bottom, one can see at the top a raised area which provides the shape of a winged beast, and on the outsides snake-like animals with gaping mouths about to swallow something round. When the flat fastening area is at the top—which is how the piece would normally be viewed–a clear stylized face with prominent round eyes, a nose, and a smiling mouth is visible.

Example D is a very large (63mm long) bronze strap end found near Blackpool, north of Liverpool. While the decoration is fundamentally a Borre knot chain with deep contours, there is a clear stylized face featuring a frowning expression with a prominent nose created by joined knot triangles. Below that appears to be a grimacing mouth. A typical Borre knot chain involves a deliberate symmetry, involving loops of an equal size (see the darker example), whereas this one is much larger at the top, emphasizing the asymmetrical face element. The difference is subtle, but quite visible.

In each example, the face of the being displayed is mysterious: the features are either just hinted at by a shortage of details, or obscured by stylized features which distance us from a human-like representation. Whether the Norse believers in Odin and Thor saw one as more human-like and relatable, and the other as enigmatic and less so is open to question, but that difference wouldn’t surprise me.

Note: after publishing Eadric And The Wolves: A Novel of the Danish Conquest of England and Viking Warlord: A Saga of Thorkell the Great have published his third novel: The Viking Woman of Birka.

See for latest news on David Mullaly on his Facebook page.

See for other articles written by him about Viking Age artefacts on:

https://psu-us.academia.edu/DavidMullaly

November 4th 2019

Exhibition We Vikings in the Fries museum *****

Yet another exhibition about the Vikings? One would think it light in the last decade with all the Viking violence that has flooded us via museums and festivals etc. How the Viking crack can still be pleasantly surprised becomes clear during a visit to Wij Vikingen in the Fries Museum.

Admittedly: the undersigned is of course spoiled rotten and not representative of the average visitor. A museum must come from a good home if it is not easily surprised by beautiful objects, if it is to be taken by the scruff of the neck and not let go. That is exactly what happens at Wij Vikingen, which lets the history of Frisians and Vikings in the coastal area of the Low Countries shine upon us in a chiaroscuro.

First of all, the title of the exhibition is well chosen: what always seemed ‘something Scandinavian’ now also appears to appeal to a national identity. And that always works well in these times. An interesting perspective is shown immediately upon entering. The coast of Friesland seen from Scandinavia. A coastline that, projected in this way, forms a much more natural-looking part of ‘the other side of Scandinavia’.

What is an exhibition without appealing objects? The Fries Museum does exactly this: exhibiting as much as possible of what has been found in this province – or just outside it. And not just the usual suspects such as the silver treasure of Wieringen or the gold bracelet found in Dorestad, but numerous ‘off the grid’ objects. Just as Scotland has The Lewis Chessmen, Leeuwarden has its own Leeuwarden chess piece. Never knew that. Recent finds such as a dragon-shaped end of a ring-brooch, found in Hallummerhoek or half of a Hiberno-Scandinavian bracelet, made in Ireland and found in Texel are shown. Beautiful golden bracteates in Scandinavian style with Odin and animal figures from the terp area of Friesland or a glass bead necklace with an enamelled cross from the early Christian period, they show a very diverse jewellery and utility splendour that takes you back to other times. Cloak pins in Jellinge style; these were also found in Friesland, or diamond-shaped brooches in the Borre style. During a tour of these objects, Friesland feels more like the southern post of Scandinavia than like one of our northern provinces. A claw animal amulet, a pendant with Wodan figure, enamelled… it is all very intriguing. Was this in a depot all this time? It should be on permanent display. Such an exhibition from October to March next year is of course much too short. In addition to the native objects, objects from other countries where the Vikings and Norsemen stayed are also exhibited. However, they are complementary to the objects that steal the show: the finds from the Frisian coastal area. Far beyond the rather infantile barbaric one-sided representation of matters that people often want to convey about this Viking age, these objects speak for a highly gifted, refined, creative culture that deserves much more study and attention.

The second pleasant surprise is that this exhibition is simply one for adults. Of course, there are also all sorts of things organised for children, but nowhere does this overpower the design. And yes, behind me I suddenly see a man in shirtsleeves with a plastic Viking helmet on who, together with someone else, grabs a fake sword and sees their own shadows projected on a wall, making it look like you are fighting as a Viking and then you have to take pictures of that. It turns out that this cannot be eradicated completely, but they remain – thanks to Odin – incidents. In a replica – to scale – Viking ship, a seated tour is given and an explanation is given of what it was like on such a ship. Around it are display cases with various coin treasures that are beautifully lit. There is still a downside to the exhibition: not all objects are shown to their best advantage due to somewhat poor placement and lighting; sometimes the dark Middle Ages are given too much honour. But lo and behold.. another pleasant surprise: the accompanying exhibition book

Wij Vikingen – Frisians and Vikings in the coastal area of the Low Countries. This does exactly what it should do: provide further explanation in text and – and above all: show all those beautiful objects – here now – beautifully illuminated, enlarged. Hurray.. hurray! This is what you’ve been waiting for. Beautifully designed – of course, there must have been a budget for it, as evidenced by the daily advertisements on public broadcasting on TV, but compiling such a book is also an art in itself. It has truly become one of the most beautiful exhibition catalogues/publications I have ever seen. This is the way it should be done!

A jewel in every bookcase or on the reading table.

The Fries Museum has done exactly what it had to do. Returning treasures found on site to the light of day and thus showing a part of our history in all its glory. Let it also be an encouragement to metal seekers to show their finds on loan – whether or not temporarily at an exhibition. How much richer we have become in our knowledge of objects thanks to these seekers. Please show them. For the sake of beauty, for research, for our historical awareness!

There is definitely more than Rembrandt and Van Gogh.

Of which note.

November 28th 2018

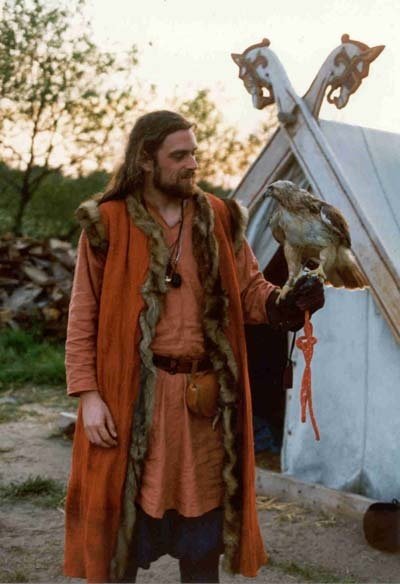

About horses and gable top signs..

For a number of years now I have had the pleasure of knowing the east of the country and getting to know it even further. Here you see all kinds of things that embody the connection with the pre-Christian. Gable top signs on farms and barns are an example of this. Below you see my dream house. Having moved last year from the increasingly crowded The Hague to Zwolle, I can already enjoy the peace and space that is here, but one must keep a dream in the offing. Apart from that I have experienced once again that it is good to change your place of residence once every 10 or 15 years.

Back to the dream house below. It is located somewhat remote, near Nutter in the Twente Dinkelland in the typical ash/coulisse landscape of these regions. The wooden roof molding is embellished by a so-called gable top sign, with two crossed horses.

The horse head motif is a very old motif. The oldest horse heads that have been preserved – from a find in a well of the rampart castle Altenberg in Hessen-Nassau – date from the last century BC and are considered Germanic. The origin of the wooden horse heads as facade decoration is somewhat obscure, as will become apparent later. It is sometimes stated that they originate from the horse skulls on poles. In German these ‘Neidstangen’ are known and already appear in old Norse texts. The horse head construction has a function of warding off evil and is called ‘nidhstaong’ in these texts: various main characters from sagas try to drive away opponents with this pole.

As late as the 1970s it is mentioned that in Schleswig-Holstein the popular belief is that a horse skull on the house and its inhabitants brings luck and prosperity. In various German areas it is known that horse skulls are placed above the stable doors in order to protect the horses present from disaster and disease. How you would think about this as a human being, if a human skull were to serve in this way, is a good second, but since a horse has a larger head, one should leave the thinking to that.

The horse skull was also well used in Poland; above the entrance door it protected against the plague.

In Northeast Twente, horse heads remained in use as a gable sign the longest, especially east of Tubbergen and north of Losser. The horse was an inseparable symbol for the Twente farmer, on which in fact his entire existence depended. In the Holtstein village of Jevenstedt there were still five houses with horse heads in 1875, one of which was called ‘Hengst’ and the other ‘Hors’. Associations with the names of the Saxon conquerors of England have been made in this context.

Nightmare

The horse heads above the entrance doors of the barn in the eastern Netherlands are also associated with the nightmare (corrupted to nightmare). Depicted as a tormenting spirit, it would sit on the bodies of sleeping residents of the house, thus obstructing their breathing. The nightmare wandered around in the form of a woman – nowadays this would of course lead to heated debates, but in the past the world was clear-cut. The witch was a woman, so was the nightmare. The nightmare was even more eager for horses and these were then deadly tired early in the morning by this uninvited rider. Originally, the nightmare was supposed to be an air elf. Mistletoe and – there they are again – crossed horse heads served to avert this disaster. The horseshoe nailed to the stable door was also supposed to have the same purpose. Scattering salt crosswise in front of the bed was also supposed to provide a solution – see the link with the crossed horse heads.

Lightning and thunder brooms

In Northern Germany and Westphalia, people believed in the lightning-deterring powers of crossed horse heads on the farmhouse. In addition to horse heads, the thunder broom gable signs bear witness to this popular belief. Until after the Second World War, there were folk storytellers who told traditional stories about ‘the Wild Hunt’ ‘an ’n heerd’, in which the horse plays a role as a destructive force that can also strike a farmhouse. The wild horse could be scared off by its own image on the house.

Problematic

In the development of horse heads, if you like: visual language, it remains problematic to find out how strongly constructive, unintentional factors played a role, and to what extent certain elements were intended symbolically. Some see the wedge-shaped ends of ridge beam supports on prehistoric Western European house shapes as the elementary initial stage of the horse head motif. People protected themselves against the evil eye by sticking their index and middle fingers up in a V-shape, as a means of defense.

Be that as it may, these types of gable top signs remain visible and appeal to the imagination, even today. Even if, like the undersigned, people knew nothing about them in particular until recently.

Want to read more?

Jans, J. and Jans, E. Gevel – en stiepeltekens in Oost-Nederland (1977).

Blog september 20th 2018

Greenlandic mythology – about a dog’s head on a human body.

Gitz-Johansen sighed, already in 1949, that young people from West Greenland had no idea what a tupilak was anymore. Progress – technical progress – in Greenland was proceeding rapidly, causing the old, original culture to die out and be forgotten. He decided, like a kind of Edward E. Curtis, to interview the ‘last of the Mohicans’ in Greenland and to record his impressions of the specific Greenlandic Inuit myths.

When – Vikings or not – from Scandinavia ‘discovered’ Greenland in 985 A.D. they were of course unfamiliar with the peoples who had lived there before them. The first inhabitants had already appeared around 2500 BC. The so-called Dorset culture manifested itself around 700 BC. This culture eventually disappeared, but the Late Dorset culture came to the island around 800 AD. and limited itself to the northwest of Greenland, to disappear around 1300 AD.

Greenland seems to have been uninhabited at the time of the first Norse settlement, but after a few centuries people did have to deal with the Inuit. The Thule-Inuit were the successors of the Dorset culture. The Iceland Annals are one of the very few sources that describe contact between the Inuit and the Norse population. Hostilities are mentioned on both sides, but archaeological evidence shows that trade must have been the main motive for encounters.

Many Norse artefacts have been found at locations where Inuit lived. Conversely, very few Inuit artefacts have been found at Norse settlements. Reasons for this have been described in very diverse ways. Indifference to the Inuit culture and decorative expressions thereof, among the Norse population, is one of them. Another is that the Norse population was only interested in perishable goods of the Inuit, such as meat and fur.

The mythology of the Inuit must have surprised the Norwegian population – if they were ever told about it at the time – but it must not have sounded completely alien to their ears. According to the Inuit of Alaska, Siberia and North America, the creator of the Earth and humanity was a raven. Because the raven has a creative function, people were also afraid of him in a certain sense. If you killed a raven, you could be sure that bad weather was in the offing.

There are differences in the stories about how the Raven ‘made’ man. For example, there are versions where he emerged from the bark of a vine. In other versions, he emerged from a pea pod. To explain the fact that the race evolved, they said that more people later emerged from the bark.

Certainly less recognizable creatures, such as Ajumaq, were of the more unpleasant kind. Half dog, half man, this dog-man monster caused everything it touched to rot and disappear. It was a creature that did not walk, but floated through the air, like a fly. I would have liked to show you a picture of this, but when I googled Ajumaq, I only got to see a beautiful lady – one has to be so careful with one’s words these days.

Another representative of this illustrious company of Inuit spirits and beings is Imap Ikua, who watches over the sea as an alternative Lorelei. The bad deeds of mankind appear as mud in her hair. Therefore she is angry, and collects all the seals in her hair, where they live as lice. From this it follows that, when the hunt is not successful, a sorcerer must dive for her, and comb her hair clean. Then she releases the seals and the hunters are successful again with the hunt.

As one of the last of the Mohicans in 2018, I spotted this outdoor exhibition in Quaqortoq. Inspection with binoculars revealed that we were dealing with an old-fashioned Inuit tanner, who kept a very alternative washing line. I was actually surprised not to have seen these scenes again. But anyway, it has been recorded again, for posterity. What remains of deep-sea monsters were hanging out to dry, besides the seal skins, has not become clear to me.

Hunting remains, even today, a risky business. After all, on the highest mountain peaks live small naked monsters, Makakajuit, always on the lookout for hunters when they come home from the hunt. As soon as they see a hunter coming home with prey, they fall on him and devour him.

Apparently this hunter was lucky this time.

Finally, the tupilak, which I bought as an amulet in Narsarsuaq, has a decidedly less poetic origin.

Tupilak is an evil spirit, which is created by sorcerers or witches. Bones of animals or birds were collected together and buried and hidden in a secluded place. When one day the sorcerer can no longer restrain himself, he visits the pile of bones and tinkers them together in the shape of a fantastic creature, but he is only allowed to touch it with his thumb and little finger, otherwise the tupilak loses its magic power.

It continues illustriously, ‘As he is reciting magic words over it, it draws nourishment from the sorcerers sexual part’.. an inflatable doll avant la lettre?

When it has acquired the desired shape, he sends Tupilak into the sea. One day, when the need arises, he issues a curse and orders it to go and kill its enemy. The latter usually dies at the mere sight of the tupilak’s terrifying shape.

In the Netherlands we have pretty much lost all faith, but those were illustrious times of faith, there in the far northwest of Europe. Still boring, if one would no longer believe in anything..

Read more (selective biography):

Gitz-Johansen: Figurer I Grønlandsk Mytologi – 2009;

Matthews, J. The Shamanism Bible – 2013

September 7th 2018

Where did Erik the Red stay and why did the Norwegian population eventually dissapear?

Greenland and the Vikings – or rather: Norwegian newcomers – are extensively told in the sagas. The Saga of Erik the Red, for example. How he and contemporary city marketing meet, I learned on our trip to the south of Greenland.

What in Narsaq is no more than a bunch of scattered stones, with apparently little coherence, may have more history than we suspect, based on the sources. Certainly, the story of Erik the Red who sailed to Quassiarsuk – better known as Bratthalid – and established his settlement there, is well-known. The manager of the museum in Narsaq added a new insight to that.

Erik the Red settled ‘next to a mountain’. However, in Bratthalid there is no – explicit – mention of that. In Narsaq there is – at two locations where the – inconspicuous, almost concealed – remains of Norse settlements have been found directly next to a mountain – and have not yet been fully investigated. The location in the photo above looks out over the bay at the beginning of Tunuliarfik – Erik’s fjord. The stone remains lie directly next to a mountain, where – how atmospheric do you want it to be – at least 125 ravens retreated for the night towards dusk. In the far northwest of the Narsaq peninsula, there are – if possible even more inconspicuous – remains of Norse settlements. Here again: right next to a mountain.

Be that as it may, I was actually quite surprised that the Greenlanders – and I don’t mean the ubiquitous Danes of course, but the Inuit – are quite proud that these Vikings had found their country. Apparently the scale of the Vikings was of such a nature and behavior that the advantages were mainly seen: trade, first. One had something that the other needed, or at least: interesting from the point of view of secondary necessity (luxury).

Luxury

That luxury, and the need for it, for modern nostalgic reasons or not, still exists today. Although it is hardly visible on the street, skins and ivory are still exponents of these needs among the Greenlanders. The skins of seals, processed as bedspreads on beds in a 4-star hotel in Qaqortoq. A vast remnant of a polar bear, a beautifully worked tooth of a narwhal on the wall of the lobby.

Back to Erik the Red. Let me start by saying that Erik the Red did not discover Greenland, of course, just as Leif Eriksson did not discover America. But is it known that not Erik the Red, but the Norwegian Gunnbjörn Ulfson discovered the island in 900 A.D., by chance? More than three quarters of a century before Erik the Red comes into the picture. Did Erik the Red know what to look for? And not just in terms of area, but also what was lucrative about it?

Did people in Iceland know in the course of the 10th century that walruses and their ivory could become a lucrative source of income, apart from the necessary first necessities of life. Did a demand for, the movement to this inhospitable place create? And, if the demand could no longer be met, did this create the movement back to the – now called Scandinavian – countries?

Erik’s green Greenland

Erik the Red tempted his followers to come to Greenland ‘because it was green there’, as a lure, or so the story goes. But this was not far from the truth. In Erik’s time the climate was even warmer than what we experience now. Greenland does look… green. What would that have been like in an even warmer climate? Compared to the west fjords of Iceland and the fjords of Norway, it would not have looked unknown or ‘hostile’.

Many theories circulate about why the Norwegian population eventually left Greenland. The worse weather in the 14th and 15th centuries is cited. Storms could affect a large part of the population in a single day, if the men were at sea, as happened in Shetland up until the 19th century.

It is possible that the plague in Europe was a driving factor, and that more than enough – by then more comfortable – areas became available. I would like to add a theory to that. As much is a matter of follow the money, wasn’t the rise of the Hanseatic cities and the trade with them in the Baltic region also a driving factor in the gradual depopulation of the areas in Greenland involved? Trade could not only be conducted over a larger area, closer to home. The diversity of the trade goods was also of course greater than that which could be exchanged in and out of Greenland.

Given this new wealth that had been heard of elsewhere in the homelands, people were simply fed up with eating seals somewhere on the edge of the world? After all, supposed (even greater) luxury makes the grass greener on the other side.

Be that as it may, scarce, often not yet investigated archaeological traces from the Norse period, do not yet provide a conclusive answer. In Greenland today, with tourism on the rise, they are a very welcome addition to history for the Inuit. A history that is sometimes told even more than the – much older – own history, which in my opinion deserves to be explained and explained more broadly. The mythology of the Inuit alone is a very wonderful one, about which I will tell more in a next blog. Traveling north..

Sources/read more:

Seaver, K.A., The Last Vikings – the epic story of the great Norse voyagers

2010 Map of Sydgrønland Kalaalit Nunaata Kujataa South Greenland – Tema om nordboerne I Grønland – theme: Vikings in Greenland, Arctic Sun Maps –

www.arcticsunmaps.com – uniquely detailed map showing all known – even the most obscure – ruins the vikings respectively Norwegian population (and Inuit).

http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/11/why-did-greenland-s-vikings- disappear

December 8th 2017

A Viking or Anglo-Scandinavian strap end with wolf (?) and entwined snake in its jaws from England.

This remarkable tiny – 34mm x 10mm strap end from the Viking Age, found in England (Norfolk area) is a one-off. Decorated in the Urnes style with interlacing snake design, it can be addressed to the 11th century, the early 12th century the latest. The strap end seems to have attached on a small strap, considering its size. What kind of strap, or where the strap was part of, is unknown.

This artefact is once again witness to the fact to what great extent craftsman would go adorning all details of every day use objects like straps. The image depicted is that of a zoomorphic animal head (could be the head of a snake, could be another animal like a dog or wolf) holding a captured snake in its jaws. The pierced holes on the end of the strap end were for attachment on the leather.

The interwoven design of the curling snake is of great quality and is made by a very skilled craftsman within this tiny frame. The brown vaguely ‘reddish’ bronze is typical by artefacts from the Viking Age, made (and found) in England. Shown to Barry Ager, former curator in the British Museum, he reacted:

‘It does appear to be a strap-end in the form of some kind of canine, wether a dog or wolf, as you suggest, catching a snake in its jaws. Could it be Fenrir, up to his tricks, maybe? Viking examples of the type are usually decrated in the Urnes style, but this more is more naturalistic, so is presumably late in the series, later 11th centuries and stylisticaly in the Viking/Norman range’.

James Graham-Campbell adresses the design of the strap end as Anglo-Scandinavian. Shown to Kevin Leahy, Archaeological Finds Specialist and National Adviser at the Portable Antiques Scheme he responded that he would look for any parallels. Meanwhile, although the precise find spot won’t be given by the metal detectorist who found it, I have mailed the Find Liason Officers of the Norfolk area, and await their response. If new insights pop up, I will add them on this article.

In the Prose Edda, three books are mentioned: Gylfaginning, Skáldskaparmál and Háttatal.

There is an intriguing text in Gylfaginning on the relation between Fenrir and Jormungand. In chapter 34, High describes Loki, and says that Loki had three children with a female named Angrboða located in the land of Jötunheimr; Fenrisúlfr, the serpent Jörmungandr, and the female being Hel. High continues that, once the gods found that these three children were being brought up in the land of Jötunheimr, and when the gods “traced prophecies that from these siblings great mischief and disaster would arise for them” the gods expected a lot of trouble from the three children, partially due to the nature of the mother of the children, yet worse so due to the nature of their father.Gylfaginning, Skáldskaparmál and Háttatal.

In chapter 38, High says that there are many men in Valhalla, and many more who will arrive, yet they will “seem too few when the wolf comes.” In chapter 51, High foretells that as part of the events of Ragnarök, after Fenrir’s son Sköll has swallowed the sun and his other son Hati Hróðvitnisson has swallowed the moon, the stars will disappear from the sky. The earth will shake violently, trees will be uprooted, mountains will fall, and all binds will snap – Fenrisúlfr will be free. Fenrisúlfr will go forth with his mouth opened wide, his upper jaw touching the sky and his lower jaw the earth, and flames will burn from his eyes and nostrils. Later, Fenrisúlfr will arrive at the field Vígríðr with his sibling Jörmungandr. With the forces assembled there, an immense battle will take place. During this, Odin will ride to fight Fenrisúlfr. During the battle, Fenrisúlfr will eventually swallow Odin, killing him, and Odin’s son Víðarr will move forward and kick one foot into the lower jaw of the wolf. This foot will bear a legendary shoe “for which the material has been collected throughout all time.” With one hand, Víðarr will take hold of the wolf’s upper jaw and tear apart his mouth, killing Fenrisúlfr.

Could this strap end depict the arriving of the wolf Fenrir with its sibling Jörmungand?

November 27th 2017

Romanesque art in the Netherlands

Through progressive insight we see the beauty around us. Often in places where you don’t expect it..

Two trips along the way, which eventually ended at a church in Vries, in the province of Drenthe, in the northeast of the Netherlands..

In August 2015 we made a bike ride to the so-called Scandinavian Village – a holiday park – just below the city of Groningen on the lake at Paterswolde. During the bike ride there we came through a small town called Vries. We had a bite to eat, I saw the church, quickly took a picture and we continued..

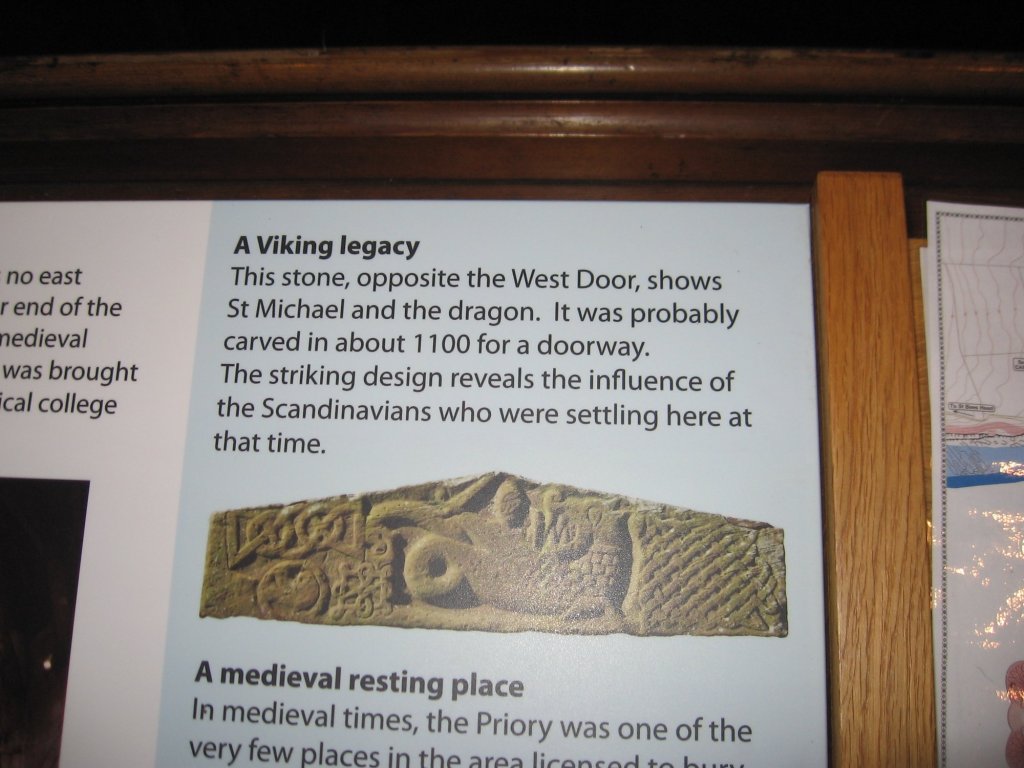

In 2015 we travelled to Cumbria in England to visit everything related to the Vikings and the early Middle Ages. But we also visited other churches from other periods and that is how we ended up at St. Bees Priory, an Anglo-Norman church with a Romanesque style entrance gate. I was immediately sold.

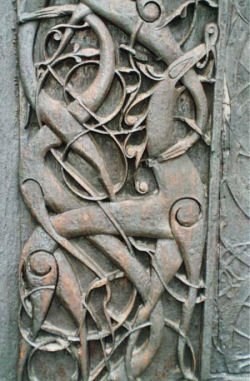

In terms of architecture and decoration style situated just after the Viking Age (1060 A.D.) and before the Gothic style (which makes its entrance around 1200/1250, it has the same, often very pure, non-bombastic art style that also attracts me in the art from the Viking Age. Often, and that is certainly the case in the early phase of Romanesque art, the depiction of animals, floral and plant motifs and the depiction of human-animal faces or animals are still stylistically connected to that Viking Age.

So.. Anglo-Norman churches, Romanesque art. But in the Netherlands? I had no idea, not at all.

In 2017 we moved from the west of the Netherlands to the east, to Zwolle. We were looking for some decoration for the wall of the living room and bedroom, and.. ended up in Vries again, this time in the workshop of Erik van Ommen, a nationally known painter and designer of bird watercolors and paintings. Again I was attracted by the church, which I now examined more thoroughly at the entrance of the church. I was astonished. I had never seen such a church in the Netherlands before. We went home with a painting and a drawing by Van Ommen, but I had to come back sometime to study the church up close.

Without realizing it was Sunday, we drove to Vries again. In the picture below and below we see the 12th century tower, the oldest part of the St. Bonifatius church (built halfway through the 12th century). Although partly rebuilt in 1769 because of brittle walls, all ornaments and arcades with bell windows and blind arcades remained intact thanks to a conservator who must have had historical knowledge of the importance of this specific church.

How lucky we were that it was Sunday and the church was open! But first I looked at the outer parts of the tower and the nave.

Imagine, look at the small open windows – still without glass in the 12th century, which would have been a novelty in the later Romanesque period, how dark the church must have been. Simply lit by candles, with a purpose of repentance, but also a sense of safety, silence.

The introduction of lancet windows into Western European church architecture from the twelfth century AD built on a tradition of arched windows placed between columns, and led not only to tracery and elaborate stained glass windows, but also to a long-standing motif of pointed or rounded window shapes in ecclesiastical buildings, which can still be seen in many churches.

Above the bell windows we see two more features of Romanesque art: the so-called chevron – zig-zag – ornament, and the pillar separation in the middle of the converging arched window, executed in an extremely simplistic way. Far removed from the rich ornamental Romanesque style. Perhaps deliberately executed in this way because there was not enough money to do it otherwise, or because a skilled – and therefore expensive – mason was lacking.

The same can be said about the doorway. Unmistakably executed in the Romanesque style, with features such as the chevron ornament and the stepped doorway. As a kind of inviting feature. One of the well-known experts in Romanesque decorative style and ornamentation, Rita Wood, saw the doorway designed in this way – as a tunnel-like tapering opening – deliberately designed in this way to create an inviting appearance for the churchgoer (or: in spe). One entered a protected shell, a protected space.

A rich ornamentation with human or human-animal figures and heads/little heads – the so-called tronies – is (still) missing here – although the term tronie refers to painting. The portal is simple, but unmistakably decorated in the Romanesque style. The so-called tympanum is also missing. This is the semicircular or triangular decorative wall surface above an entrance, door or window, which is bounded by a lintel and an arch. It often contains pediment sculptures or other statues or ornaments. In the church in Vries this part above the door entrance is filled with stones without any form of decoration.

People will always investigate things and it is thanks to Reverend Klumper that he noticed and asked himself why there were thirty-seven teeth above the doorway. Why specifically the number thirty-seven, he asked himself. This is no coincidence. In our minds we have to travel back to the time when this structure was built. When these thick Romanesque church walls were built, it was not only to support the vaults. At the same time they expressed the defense against the evil outside world. Literally and spiritually. Note the loopholes/windows on the first floor of the bell tower. They were built for that purpose and were meant to function in this way. In Romanesque art, the evil outside world was depicted with rich ornaments and anthropomorphic – half human half animal – details under the capitals. Floral motifs and (interwoven) snakes were all part of this image.

Due to a lack of money in the small village of Vries, these ornamental and bombastic features are missing here. To depict an alternative element of defense against evil, numerical symbolism was used that the congregation could and would understand.

In addition to the thirty-seven serrations, there are eighteen arcades on the south wall and nineteen on the north wall. Both form the same number of thirty-seven. The eighteen arcades are symbolic of light, life, the sun and good, and to the right of the entrance. The right side is the so-called Good Side, because from the right side of Christ flowed his redeeming blood. The nineteen arches symbolize the Bad Side: darkness, death, the moon and evil. Not much good came from the north, as the preceding Viking Age had shown.

The highlight of the journey of discovery in the church revealed itself when we entered the church and walked through the nave to the rear.

Allow me to consider this as a Holy Grail of an unexpected example of Romanesque art in the Netherlands. Where was this magnificent baptismal font actually made? A brochure in the church provided clarity. In the early Middle Ages, there was a sandstone quarry just across the border in nearby Bentheim in Germany. These baptismal fonts were made at the same location and sold to Hanseatic cities such as Zwolle and Deventer. But of course, these cities were not yet called that at the time of production. So a minister from Vries bought this baptismal font, transported it, as far as Meppel, over water, but after that it must have been transported by horse and cart..

Bentheim produced many baptismal fonts, the twenty-six baptismal fonts that have been found in the Netherlands testify to this. Seventy-five baptismal fonts are known from East Frisia, Schleswig-Holstein, Oldenburg and Westphalia. Most of them are still in their original location and are used for baptisms..

The baptismal font in the church of Vries is typically Romanesque: not highly ornamental, but ‘honest’ in its execution. Like all ornaments in the Romanesque parts of the church. The cupa – the bowl – has various ornaments in a so-called rope motif, a band of vines, grapes and leaves. The execution is highly stylised but cleverly executed. In addition to the band below, stylised Acanthus leaf ornaments can be seen. This is a Greco-Roman type of motif. The fruit-bearing wine grape is symbolic of life flourishing through faith in God, which begins with Christianisation at the baptismal font. The four human figures at the feet of the baptismal font are not specific figures. Their hands resting on their thighs carry and support the baptismal font. Note the same type of eyes on the so-called Lewis chessmen – a set of chess pieces from the 12th century found on the Scottish island of Lewis. The baptismal font can be dated to the beginning – or possibly a little later – of the 12th century. The baptismal font in the church in Vries was loaned free of charge by the Drents Museum and that is why we can admire it in its original place ‘in situ’. In the museum of Assen there are still six Romanesque baptismal fonts to be viewed.

At the back of the church in the choir there are two sarcophagi, sunk into the pavement. They date from the 12th/13th century. These sarcophagi were used to decompose the body of a person. Sarca phagein = eating meat. After the body had decomposed it was placed elsewhere. These sarcophagi were originally outside the church with the lid facing upwards.

Finally, take a look at the exceptionally old and shaped lime trees on the square in front of the church.

April 20th 2017

A Viking myth and a belt mount

This week’s blog is a guest blog written by David Mullaly, wich I thank him for greatly.

One of the most widely known Norse myths, which provided a cornerstone for the Vikings’ beliefs about their origins, involves the story of Sigurd, a famous hero, and Fafnir, a fearsome dragon which guarded a great treasure. Making a long story very short, Sigurd digs a pit, and when the dragon falls into it, Sigurd stabs it with his well-tested sword Gram, and kills the beast.

The two pictures provide a clear image of a square bronze belt mount, found in the Kievan Rus area of Eastern Europe, which shows clear traces of gilding, and the remains of four fastening posts on the reverse. Almost all of the openwork mount is filled with the body and central head of a beast, presumably a variety of serpent or dragon. The head is identical to heads of beasts which are associated with the Borre style of Norse decoration.

In fact, the Borre style is probably the most commonly Viking style found on clearly Scandinavian items in Eastern Europe, since the Swedish Vikings who travelled east to both explore and in some cases settle did so primarily in the 9th and early 10th centuries, when the Borre style was predominant in Sweden and the rest of Scandinavia.

However, if you look closely at the bottom left of the square, you can see an almost circular swirl of lines surrounding what may be a human figure. Note that there are hatching lines or similar etched details covering the dragon, and the swirling lines in the corner are different. Also, if you look to the right of the figure, you see a thin horizontal element, highlighted by the open areas around it. That element is unlike anything else in the scene, and seems to connect the human figure with a leg or foot of the beast.

I would suggest that the mount portrays the killing of the dragon Fafnir by the hero Sigurd using his named sword Gram. The horizontal element is likely the sword, and Sigurd is shown stabbing the beast with it. Although other theories are possible, this one seems to be the best fit for what we see here.

Isn’t it remarkable that a craftsman devoted so much time to the decoration on a small bronze mount like this? What may be more remarkable is that there are very few known representations from the Viking period of Sigurd and Fafnir, one of the truly seminal myths of that culture. As far as I am aware, this is the only known example of this fascinating mount.

November 20th 2016

An Anglo-Scandinavian horse harness pendant in Ringerike style

This blog I like to show you an interesting horse harness pendant from England from the Viking Age.

But first a short prequel. On a regular basis I am writing about my artefacts in the magazine of the so called ‘Viking Genootschap’ in Belgium, The Ravenbanier. I was writing the article for the magazine for January 2017 about another horse harness pendant I have – see here – as I started to Google on ‘Viking horse harness pendant’. Googling on ‘Viking’ and adding words to that, have costed me a lot of money the last ten years but gave me the joy of the world also..

Googling so, I stumbled on this horse harness pendant on an auction website Ebid, where I was surprised to be able to buy this one for a fixed prize. Of course I was tempted and seduced once more..

The horse harness pendant is one stylistically to be addressed as Anglo-Scandinavian in a – derived – Ringerike style. The overall execution of the pendant is ‘crude but charming’. A true Scandinavian craftsman would have made a far more clever, symmetrical and well executed piece. As here, this isn’t the case I would suggest that this horse harness pendant very possibly was made by or a Anglo-Saxon smith making the pendant in a deliberate Scandinavian stylish way to appeal to the taste of the Scandinavian settlers in England or was made by a successor of one of the Scandinavian settlers in England. Not being familiar in a direct way with the Scandinavian way of art, he might have attempt to imitate the Ringerike styleform.

(the candle in the photograph: I kept it this way, as everyone can use some extra light in these dark weeks to come..).

Interestingly if we turn the pendant 180 degrees upsidedown, we can distinguish also a ‘fleur the lis’ – clumsy executed as it might be – symbol. Now, being addressed to the 10th-11th century I like to argue even for a transverse/hybrid Anglo-Scandinavian / (Anglo-) Norman art style as by the use of this symbol. Also if one is considering one of the ‘fleur the lis’ variants as can be seen underneath this blog, one could easily see the horseheads as the form of the outward curlings of the fleur the lis, adding to the crude symbol on top (if turned 180 degrees) of the horse harness pendant. But – again – any remarks or alterations are welcome.