Raven penny aanvullen

Viking “St. Edmund memorial” penny

aanvullen keerzijde

One of the classic Viking silver pennies made in England, the St. Edmund Memorial penny was issued by the Vikings in Danish East Anglia to appeal to the Christian residents who had come to revere as a saint the former King Edmund. He had been killed by the famous sons of Ragnar Lothbrok, Ivar the Boneless and Ubbe, about twenty years previously, when the Viking Grand Army swept through that part of the country. Although rumours persist that he was killed by the Blood Eagle form of torture, it’s likely that he was simply full of arrows, perhaps as a test of the strenght of his Christian religion. The Vikings made serious efforts to live peacefully with the residents of areas in England that they had conquered, and this coin is a perfect example of that sort of effort. The obverse reads SC EADMUND REX around the letter A. The reverse reads ADRADUS MONE (” Adradus made me” using an upside down M). Many examples of this issue display meaningless letters – this one actually provides the name legibly.

The weight is 1.21 grams, made 895 – 910 AD (19 mm) with very attractive dark toning.

Edmund the Martyr (also known as St Edmund or Edmund of East Anglia, died toning. classic was king of East Anglia from about 855 until his death.

Almost nothing is known of Edmund. He is thought to be of East Anglian origin and was first mentioned in an annal of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written some years after his death. The kingdom of East Anglia was devastated by the Vikings, who destroyed any contemporary evidence of his reign. Later writers produced fictitious accounts of his life, asserting that he was born in 841, the son of Æthelweard, an obscure East Anglian king, whom it was said Edmund succeeded when he was fourteen (or alternatively that he was the youngest son of a Germanic king named ‘Alcmund’). Later versions of Edmund’s life relate that he was crowned on 25 December 855 at Burna, (probably Bures St. Mary in Suffolk) which at that time functioned as the royal capital, and that he became a model king.

In 869, the Great Heathen Army advanced on East Anglia and killed Edmund. He may have been slain by the Danes in battle, but by tradition he met his death at an unidentified place known as Haegelisdun, after he refused the Danes’ demand that he renounce Christ: the Danes beat him, shot him with arrows and then beheaded him, on the orders of Ivar the Boneless and his brother Ubbe Ragnarsson. According to one legend, his head was then thrown into the forest, but was found safe by searchers after following the cries of a wolf that was calling, “Hic, Hic, Hic” – “Here, Here, Here”. Commentators have noted how Edmund’s death bears resemblance to the fate suffered by St Sebastian, St Denis and St Mary of Egypt.

A coinage commemorating Edmund was minted from around the time East Anglia was absorbed by the kingdom of Wessex and a popular cult emerged. In about 986, Abbo of Fleury wrote of his life and martyrdom. The saint’s remains were temporarily moved from Bury St Edmunds to London for safekeeping in 1010. His shrine was visited by many kings, including Canute, who was responsible for rebuilding the abbey: the stone church was rebuilt again in 1095. During the Middle Ages, when Edmund was regarded as the patron saint of England, Bury and its magnificent abbey grew wealthy, but during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, his shrine was destroyed. The mediaeval manuscripts and other works of art relating to Edmund that have survived include Abbo’s Passio Santi Eadmundi, John Lydgate’s 14th century Life, the Wilton Diptych and a number of church wall paintings.

Viking Kingdom of York, “Hunedeus and Cnut”, ‘Cunetti’ Group (c.895-902), Penny, 1.42g., York mint, small cross with pellet in 1st and 4th angle, +CVNNETTI around, rev., CR T EN (Cnut Rex) around patriarchal cross, with a pellet in angle of the smaller cross.

The inscription

The king’s name, CNVT – Cnut, is written in such a form that you make the sign of the cross when you read it, as in a blessing – up, down, left, right – and between these letters is the word REX (‘king’).

In the centre is a large and elaborate ‘patriarchal’ cross that had special meaning for the Church. On the other side, the inscription reads MIRABIL[I]A FECIT, which is Latin for ‘He has done wonderful things’ – a quotation from Psalm 98, v.1.

The Viking kingdom of York

The Scandinavian micel here (‘great army’) arrived in England in 865 and for years it moved from one region to another attacking, stealing and even conquering. The Viking kingdom of York was established in 876 by Halfdan, one of the leaders of the army.

The coinage is one of the few sources of evidence which have survived about the kingdom. It is surprising to find that some of Halfdan’s successors in the late 890s and early 900s were producing a large coinage that was more overtly Christian than any other in Europe at that time.

The Christian and Viking imagery on the coinage

The Christian symbolism on this and other York issues of the period shows that the new Scandinavian kingdom not only adopted Christianity towards the end of the 9th century, but saw it as politically correct to publicise it.

They wanted to demonstrate to their Anglo-Saxon, Carolingian and Celtic neighbours that they possessed qualities which would link them to the block of civilised Western states.

In the 920s, faced with the threat of reconquest by the Anglo-Saxons, the Viking kings of York saw a resurgence of Norse nationalism when symbols such as Thor’s hammer and ravens with spread wings appeared on the coins.

A dual bullion economy

A dual economy existed in Danelaw which typified the blending of Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian cultures characteristic of the region.

Despite the sophistication of the York coinages, the traditional ‘bullion’ economy survived in the Scandinavian community. For some purposes transactions were conducted with silver weighed out, rather than using coins at their face value.

So we find hoards containing a mixture of Viking coins, foreign coins such as Islamic dirhems brought across Russia and Scandinavia, and ‘hack-silver’ – cut pieces of silver plate and ornaments.

Viking period coin of Aethelred ‘second hand type’ 985 – 991 AD face to the right with scepter

Æthelred the Unready, or Æthelred II (circa 968 – 23 April 1016), was king of England (978–1013 and 1014–1016). He was son of King Edgar and Queen Ælfthryth and was only about ten years old (no more than thirteen) when his half-brother Edward was murdered. Æthelred was not personally suspected of participation, but as the murder was committed at Corfe Castle by the attendants of Ælfthryth, it made it more difficult for the new king to rally the nation against the military raids by Danes, especially as the legend of St Edward the Martyr grew.

From 991 onwards, Æthelred paid tribute, or Danegeld, to the Danish King. In 1002, Æthelred ordered a massacre of Danish settlers. In 1003, King Sweyn invaded England, and in 1013, Æthelred fled to Normandy and was replaced by Sweyn, who was also king of Denmark. Æthelred returned as king, however, after Sweyn died in 1014.

“Unready” is a mistranslation of Old English unræd (meaning bad-counsel)—a twist on his name “Æthelred”, meaning noble-counsel. A better translation would be ill-advised.

Viking period coin of Aethelred, 991 -997 AD face to the left type with scepter

Viking period coin of Aethelred (978 – 1016 AD)

Notice the peckmarks on the coin.

The small gouges on the reverse of the coin are known as ‘peck’ marks and were made with a knife to test the purity of the silver. The Anglo-Saxons would have had no need to do this, as the bust of Æthelred on the coin was a royal guarantee of its value: this coin could be exchanged for a penny worth of goods. The Vikings, however, only saw the coin for its silver content and pecked or bent it to find out how soft, and therefore how pure it was.

See publication on Aethelred coin from the Fitzwilliam Museum

Those who are able to examine such coins may well notice a small scar or groove incised in the surface of some of them. These are known as ‘peck’ marks and embue such coins with some of the drama of Aethelred’s reign. Vikings had the habit of digging the point of their daggers into coins to assure themselves that they were of solid silver.

See publication Saxon and Vikings (the mint)

Viking ‘ Quatrefoil type’ penny of Canute (Knut) 1017-1023 A.DCNUT REX ANGLORU[M]” (Cnut, King of the English)

Cnut the Great (Old Norse: Knútr inn ríki; c. 985 or 995 – 12 November 1035), more commonly known as Canute, was a king of Denmark, England, Norway, and parts of Sweden, together often referred to as the Anglo-Scandinavian or North Sea Empire. After the death of his heirs within a decade of his own and the Norman conquest of England in 1066, his legacy was largely lost to history. Historian Norman Cantor has made the statement that he was “the most effective king in Anglo-Saxon history”, despite his not being Anglo-Saxon.

Cnut was of Danish and Slavic descent. His father was Sweyn Forkbeard, King of Denmark (which gave Cnut the patronym Sweynsson, Old Norse Sveinsson). Cnut’s mother was the daughter of the first duke of the Polans, Mieszko I; her name may have been Świętosława (see: Sigrid Storråda), but the Oxford DNB article on Cnut states that her name is unknown.

As a prince of Denmark, Cnut won the throne of England in 1016 in the wake of centuries of Viking activity in northwestern Europe. His accession to the Danish throne in 1018 brought the crowns of England and Denmark together. Cnut maintained his power by uniting Danes and Englishmen under cultural bonds of wealth and custom, rather than by sheer brutality. After a decade of conflict with opponents in Scandinavia, Cnut claimed the crown of Norway in Trondheim in 1028. The Swedish city Sigtuna was held by Cnut. He had coins struck there that called him king, but there is no narrative record of his occupation.

The kingship of England lent the Danes an important link to the maritime zone between the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, where Cnut, like his father before him, had a strong interest and wielded much influence among the Gall-Ghaedhil.

Cnut’s possession of England’s dioceses and the continental Diocese of Denmark – with a claim laid upon it by the Holy Roman Empire’s Archdiocese of Hamburg-Bremen – was a source of great leverage within the Church, gaining notable concessions from Pope Benedict VIII and his successor John XIX, such as one on the price of the pallium of his bishops. Cnut also gained concessions on the tolls his people had to pay on the way to Rome from other magnates of medieval Christendom, at the coronation of the Holy Roman Emperor. After his 1026 victory against Norway and Sweden, and on his way to Rome for this coronation, Cnut, in a letter written for the benefit of his subjects, stated himself “king of all England and Denmark and the Norwegians and of some of the Swedes”.

Hiberno-Norse Kings of Dublin, Sihtric Anlafsson ‘Silkenbeard’ (c.989/995–1036), Phase III (c.1035-c.1060), Dublin mint, Penny

By about 1035 AD the coinage minted in Dublin had degraded to a point where it is likely that it was only being produced for internal use within Ireland as it had fallen below the standards used in any neighbouring regions. The coins are smaller and of poorer silver, they have legends made up of strokes and symbols rather than lettering, the symbol of the human hand appears on many coins in one or more commonly two quarters of the reverse cross.

The native Irish had no culture of coinage and their experience with the brief earlier issues was clearly insufficient to enable them to continue minting to a high standard following the transfer of power from the Dublin Vikings to the native Irish chieftains and High Kings.

This phase of Hiberno Norse coinage continued until about 1060 AD.

Hiberno-Norse coins were first produced in Dublin in about 997 AD under the authority of King Sitric Silkbeard. The first coins were local copies of the issues of Aethelred II of England of England, and as the Anglo-Saxon coinage of the period changed its design every six years, the coinage of Sitric followed this pattern.

Following the Battle of Clontarf in 1014 AD the Hiberno-Norse coinage ceased following this pattern and reverted to one of its earlier designs—the so-called ‘long cross’ type. Coins of this general design (with occasional new designs incorporated briefly from other English and European issues) were struck in decreasing quality over a period of more than 100 years. By the end of the series the coins had become illegible and debased, and were too thin to serve for practical commerce.

All the coins produced were the penny denomination. They were initially produced at the penny standard (i.e. one pennyweight or 1/240th of a pound of silver) but the later pieces are both debased and lightweight.

I bought this one many years ago on Ebay for a very suitable price. Although struck in two, it doen’t infect the value of this (though the more common type under the Hiberno-Norse coinage) penny. In the viking age, coins were split in two, more than once, using it as a part of weight (hack silver), or just “as a half penny”. As there were no half penny’s, they splitted them into two.

Also see link to Irish coinage during viking times

Sigtrygg II Silkbeard Olafsson

Sigtrygg II Silkbeard Olafsson (also Sihtric, Sitric and Sitrick in Irish texts; or Sigtryg and Sigtrygg in Scandinavian texts) was a Hiberno-Norse King of Dublin (possibly AD 989–994; restored or began 995–1000; restored 1000 and abdicated 1036) of the Uí Ímair dynasty. He was caught up in the abortive Leinster revolt of 999–1000, after which he was forced to submit to the King of Munster, Brian Boru. His family also conducted a double marriage alliance with Boru, although he later realigned himself with the main leaders of the Leinster revolt of 1012–1014. He has a prominent role in the 12th-century Irish Cogadh Gaedhil re Gallaibh and the 13th century Icelandic Njal’s Saga, as the main Norse leader at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014.

Sigtrygg’s long reign spanned 46 years, until his abdication in 1036. During that period, his armies saw action in four of the five Irish provinces of the time. In particular, he conducted a long series of raids into territories such as Meath, Wicklow, Ulster, and perhaps even the coast of Wales. He also came into conflict with rival Norse kings, especially in Cork and Waterford.

He went on pilgrimage to Rome in 1028 and is associated with the foundation of Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin. Although Dublin underwent several reversals of fortune during his reign, on the whole trade in the city flourished. He died in 1042.

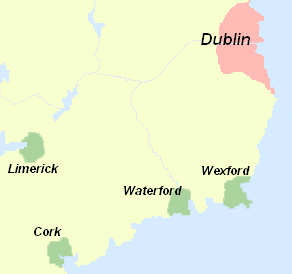

GREEN: The Viking settlements of Cork, Limerick, Waterford and Wexford

(Part of the Kingdom of Munster, under the control of Boru)

PINK: The Kingdom of Dublin, under the control of Sigtrygg